March 2020 Latinx Talk Special Series on Latinx Migration Literature

When the protagonist, Juan Marcos, in the opening pages of Guillermo Cotto-Thorner’s little-known, Spanish-language novel Trópico en Manhattan (1951), migrates from Puerto Rico to New York City, he is welcomed at the airport by his host, Antonio, a working-class Puerto Rican who had migrated to the city over a decade before, in the 1930s. Together, they head to Antonio’s home in El Barrio, the then predominantly Puerto Rican neighborhood in Harlem. Riding the subway for the first time in his life, amid the noise, commotion and clamor, Juan Marcos is both culturally and linguistically bewildered. Antonio, on the other hand, long accustomed to the sights and sounds of New York, amusedly guides the newcomer. It is the first of many scenes that will underline the subtle yet powerful differences between recent arrivals from Latin America and those who migrated long ago, conveying how migration is a process that deeply transforms who we are and how we relate to the world around us, while also acknowledging that migration affords us a gradual development of community, in which “los acabaditos de llegar” eventually become “los veteranos,” establishing the groundwork and networks of support for those who will come after.

Although nearly forgotten today, Trópico en Manhattan is of remarkable historical significance as the first novel to document the Puerto Rican mass migration to New York City. This significance was recognized early on. In the late 1960s, the novel was briefly incorporated into the Department of Education of Puerto Rico’s secondary-school curriculum, and was taught alongside other now-classic works about Puerto Rican migration, including René Marqués’ play La carreta (1953) and Pedro Juan Soto’s short story collection Spiks (1956). Written and published while Cotto-Thorner was living in New York, Trópico en Manhattan draws heavily from the author’s own personal experience of migration. Guillermo Cotto-Thorner was born in Puerto Rico in 1916 and arrived in New York in 1938, becoming, like his father, a Protestant minister. His church work granted him intimate contact with Hispanic parishioners, and he distinguished himself as a tireless social advocate and progressive leader in the burgeoning Latinx community. He wrote regularly for the New York Spanish-language press, and his politically progressive sermons were collected in 1945 under the title Camino de Victoria. By 1950, he had completed an early draft of his novel, which was published shortly thereafter, just as the Puerto Rican mass migration intensified. As such, the novel captures the Puerto Rican mass migration as it was taking place, and as lived by one of its participants.

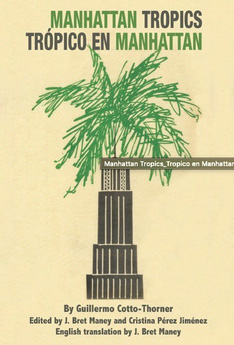

With this keen, internal perspective, Trópico follows the intertwined stories of Juan Marcos and Antonio and explores a series of themes that continue to affect present-day Latinx communities: the challenge of finding affordable housing, the search for steady employment and a living wage, the effort to counteract stereotypes and discrimination, and the desire to build lasting pan-ethnic coalitions. Importantly, while the novel exhibits the trials and pains of migration, it also discloses its joys and cultural rewards. Against the morbid view of migration painted by many of the author’s Puerto Rican literary contemporaries, who presented migration solely as a narrative of cultural loss, Trópico en Manhattan celebrates New York City as a fertile ground for Puerto Rican culture, and, more broadly, for Latinx cultural identity. The novel’s cover, with its lush palm tree sprouting from the Empire State Building, the city’s most iconic skyscraper, captures the way the “tropics” can be transplanted, and bloom and flourish, in Manhattan. For all that migration involves dispersal and painful uprooting, Cotto-Thorner’s novel reminds us it is also a replanting, one which engenders thriving, new cultural forms and identities.

This affirming portrait of diasporic life is already in evidence on Juan Marcos’s first day in the city as he exits the subway and walks toward Antonio’s home. He is surprised that his foreign surroundings, defined by uncannily monotonous rows of brick buildings and gray, grid-like streets, are in fact familiar. Puerto Rican kids play stickball in the streets, Spanish-speaking men joke and play checkers on card tables on street corners, storefronts advertise Puerto Rican fried foods, a man with a wooden cart sells coconuts and shaved ice, the classic Puerto Rican song “El Lamento Borincano” plays in the background. Yet, as much as the streets of El Barrio seem an overseas extension of Puerto Rico, they are also something new entirely. Taking it all in, Juan Marcos notices two women carrying grocery bags. “They’re coming from the marqueta,” Antonio explains, but Juan Marcos is unable to understand this strange word, a sample of the many enriching linguistic inventions and new cultural expressions and identities germinating in diaspora and documented in the novel. With remarkable foresight and to considerable stylistic effect, Cotto-Thorner’s novel deploys such practices of code-switching, which the author terms “Neoyorquismos,” all of which help position Trópico en Manhattan as an important forerunner of the bilingual aesthetics found in Nuyorican writing and much Latinx literature today.

Available for the first time in an English translation, this novel deemed a “long-neglected American classic [that] is truly a gift” by Ernesto Quiñonez, the author of Bodega Dreams, is now available in a bilingual edition from Arte Público Press’s Recovering the U.S. Hispanic Literary Heritage Series.