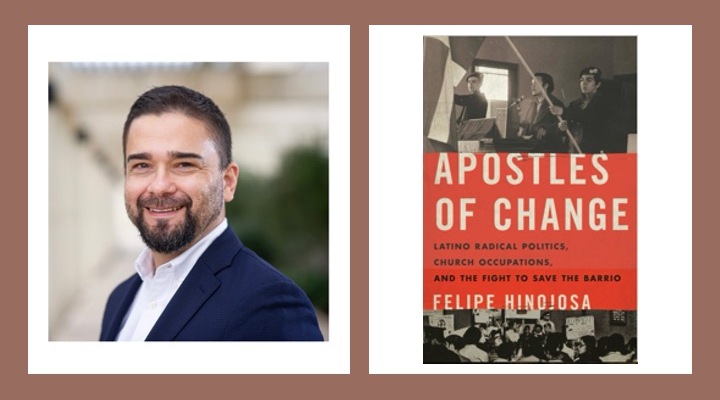

Apostles of Change: Latino Radical Politics, Church Occupations, and the Fight to Save the Barrio

by Felipe Hinojosa (University of Texas Press, 2022)

Theresa Delgadillo: Your first book was about the ways that the 1960s civil rights movement took hold within the Mennonite church, creating greater Black and Latinx-focused programming in the church and winning support for the movement among Mennonites. Is Apostles of Change a kind of prequel that considers how this movement within the church became a possibility?

Felipe Hinojosa: That’s exactly right. Whereas my first book focused on religious leadership and politics within one particular religious group, Apostles takes a step back to examine the larger social and political dynamics in the postwar era that placed the church at the center of Latina/o urban politics. Writing Apostles really forced me to become an urban historian (which I have embraced) to address how urban renewal, migration, and Latina/o radical politics all intersected with mainline Protestant and Catholic churches in the 1960s.

Theresa Delgadillo: What does Apostles of Change give to readers?

Felipe Hinojosa: I think readers will come away with a fresh understanding of the Latinx Freedom Movement across the U.S. In particular, I think readers will come away with a deep sense for how Latinx radicals in four of America’s largest cities clashed, negotiated, and collaborated with religious leaders as they pushed back against the devastation brought on by urban renewal. I also hope readers are moved to reflect on the good that religion can do in politics. I know that might seem impossible, but I do believe religious politics in the 1960s and 1970s offer us new visions, new possibilities for faith politics. I also hope readers are inspired with the pragmatism and brilliance of Latinx radicals.

Theresa Delgadillo: In considering religious actors beyond the clergy and the significance of local struggles on national religious institutions, does Apostles of Change hold out hope for the renewal of religious institutions today?

Felipe Hinojosa: Latinx radicals saw an oppressive religious institution, but they also saw possibilities for community control, they envisioned a new church space, and rather than giving up on the church, rather than seeing it as only a colonial institution, they transformed it into the people’s church. That certainly gives me hope.

Theresa Delgadillo: Both of your books focus on the 1960s and 1970s. What is it about this period that interests you? Will you continue working on this period?

Felipe Hinojosa: I was born and raised in a U.S./Mexico border town, in Brownsville, Texas, in a church that cared deeply about the community. The lessons I learned in that church–love, service, and justice—remain with me to this day. I think that’s what keeps me fixated and obsessed about the 1960s and 1970s. I love the imagination, the negotiations, and the dreams that were born in that era. I love that, even as I am critical of the missteps and problems of the era and its leaders. I want to tell stories that are honest about the pain, the loss, the hurt, the abuse, the displacement even as I write about hope, visions, dancing, art, music, and the organizing that made it possible to believe in social change.

Theresa Delgadillo: The in-depth consideration of local struggles and local coalitions, including across racial/ethnic groups, and the melding of archival and oral history methods that you offer in Apostles of Change seems like a new trend in Latinx and ethnic studies. Do you see it this way? How is this book in conversation with current debates in Latinx and ethnic studies?

Felipe Hinojosa: I definitely see it that way. For me it begins with my training at the University of Houston. I’ll never forget a grad seminar I took called Comparative Race and Ethnicity. Taught by Luis Alvarez, who is now a professor at UC San Diego, that class forever shaped how I think and write and research about the civil rights era. We read Natalia Molina, Nicholas De Genova, Ana Ramos-Zayas, and so many great scholars that were really pushing the field to break free from a siloed approach to Latinx studies and instead consider how horizontal relationships have shaped race, class, gender, and sexuality. That class opened my world and moved me to think about the expansiveness and beauty of Latinx studies. I’m so honored to be a part of a larger movement of scholars that is rethinking how we do Latinx history. In my corner of the world, I’m telling stories that I hope can help us better understand the Latinx experience in barrios and across the Americas.