Writing about undocumented immigrants who were deported or forced to return to Mexico has been emotionally challenging in ways that have been surprising. We belong to a generation of immigrants whose parents were able to legalize their status through the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA). We met in grad school and soon realized we had a lot in common: both of us were formerly undocumented youth whose families had been economically displaced from Mexico. We were teenagers living in the greater Los Angeles area when anti- immigrant governor Pete Wilson was in office, and when California voters approved Proposition 187. We were also first-generation college students with working-poor roots and with deep commitments to our communities. We have been friends for nearly 20 years; and it is soul-sustaining that, after supporting each other through our doctoral program, now we find ourselves doing field work on different projects about Mexican deportees and returnees.

Over the past five years, we have been moved and shaken by the individual and collective feelings that migration and deportation produce. We have become undone by the stories and the silences that have been shared in both collective and private conversations. We are fully aware that certain circumstances enabled the legalization process of our families. Yet, contrary to dominant anti-immigrant rhetoric, we know that nothing has been given to us and we have not taken anything from anybody.

As we sit across from people a few years older or younger than us, people whose voices crack when they speak of children they were forced to leave in the States, or who shed tears over being unable to be there during joyous occasions (like high school graduations and birthdays), we cry with them. We don’t try to contain nor distance ourselves in the name of objectivity. For us, research is personal and political. But it is precisely this vulnerability—part compassion, part empathy, part rage—that we offer folks because they are not simply interviewees or research subjects. Scholars have grappled with the question of ethics, proximity, and accompaniment to think about the uneven power relations that are embedded in research. In the context of Latin America, the practice of accompaniment has a long history that can be traced back to social justice movements that prioritize the needs, welfare, and liberation of the poor and oppressed (Aparicio et al., 2022). Leisy Abrego (2023) has written about accompaniment as an ethic rooted in prioritizing the people being interviewed and their well-being, emotional and otherwise. According to the contributors to Ethnographic Refusals, Unruly Latinidades, “listening in solidarity, acts of accompaniment, and witnessing are all practices that require specific kinds of careful ethnographic engagement and ethical responsibility” (Aparicio et al., xxv, 2022). As immigrants and researchers, we offer our vulnerability as part of our humanity, of bearing witness to their own struggles, tears, or voices breaking. This is not to say the lives of deportees and returnees only occur in pain or suffering— they are poets and writers, fighters and organizers, people working to create another world de este lado y del otro.

Though we recognize our privilege, the stories of Mexican deportees and returnees nos recuerdan de qué materia estamos hechas. It matters little if we are good or bad. The truth is, as a community, we have been branded. The fact is only very few in this world are privileged enough to abide by all laws, rules, and regulations. In the past years, we have witnessed a community that cries, laughs, organizes and asserts itself against its expulsion and devaluation. And we have been listening deeply and with intention.

It is important to note that the U.S. government differentiates between people it places into “removal” proceedings and those who are expelled via “voluntary departure” where a person decides to leave, often because they are in danger of being placed into removal proceedings. There are different legal consequences to each category but often there is a ban on entering the United States for several years. In the personal lives of undocumented people, however, the result is the same: expulsion and family separation. In this two-part essay, we use deportation and deportees to refer to people who underwent removal proceedings and those that engaged in voluntary departure. What we offer is not meant to be an exhaustive analysis of a multifaceted process that wrecks people’s lives. Instead, we hope to illustrate the complexity of the experience of deportation and parenting through the profiles of Ana, Michelle, Diego, and David. Though most academic research on parenting across borders has focused on transnational motherhood in the context of immigrant women leaving their children under the care of others (Hondagneu-Sotelo and Avila 1997; Dreby 2010), in this piece, we focus on the gendered experiences of transnational parenting for both deported fathers and mothers. However, rather than using the term transnational motherhood, we use “maternindad a distancia” since it was the phrase used by Ana to describe the dynamic she navigates as a mother. In part two of this essay, we have chosen to use the parallel “paternidad a distancia” to describe Diego’s and David’s experiences as fathers parenting after deportation. The experiences of the four people we write about both exemplify and deviate from much of what is imagined or represented about deportation because they fit the profile of those targeted but they are not defeated; instead, they are often advocating for social and policy changes in both countries. As immigrants and scholars, it has become increasingly urgent for us to trace and center the types of maternal and paternal subjectivities that emerge in the context of detention, deportation, or in transit.

These four people are extraordinary and ordinary. And they come from a place where we belong.

Deportación y la maternidad a distancia

As the co-founder of Deportados Unidos en la Lucha (DUL) [Deportees United in Struggle], a collective that worked with Mexican deportees in Mexico City (2016-2022), Ana Laura López has a highly visible profile; and the most basic details of her deportation case and her organizing work with DUL and against family separation can be found by googling her name. Certain comments posted to some videos and social media posts also show that there are people who think Ana must have done something wrong to “deserve” her deportation. Particularly telling are the comments that associate her tattooed body to a criminal activity or gang affiliation. These comments can be contextualized as part of a global narrative about immigrants. That is, the ideological underpinnings that make possible the criminalization of deportees in Mexico are part of a broader discursive system that, as scholars have argued, constructs migrant bodies as social threats across borders. This criminalization takes place whether migrants are in transit, in detention, or in a deportation process, or whether they are returnees or asylum seekers (Cacho 2012; Varela Huerta 2015; Speed 2019). But patriarchal ideologies and gender norms also make Ana an easy target of condemnation. As a transnational mother and now a deportee mom, she deviates from everything that we have been taught makes a “good Mexican woman” and a “good mother.” La maternidad a distancia, as Ana calls it, has marked her life. First, when she immigrated to the US and left four children with her mother. And later, when she was deported and separated from the two sons she had with her second partner.

Transnational motherhood, middle women, kin work are frequently used terms to describe the labor and social arrangements and networks necessary for immigrant mothers to maintain an intimate connection with their children while raising them across borders (Hondagneu-Sotelo and Avila 1997; Debry 2010; Tracey Reynolds, Umut Erel, and Erene Kaptani 2018). Since the 1990s, transnational motherhood has been a focal point of analysis that renders visible the complexities of migrant maternity and non-normative family formations. While family separation is perhaps one of the greatest costs of migration, for women who leave their children in their countries of origin, migration has often represented the possibility of providing better futures for their kids. Transnational motherhood contradicts dominant notions of proper or natural ways of mothering (Hondagneu-Sotelo and Avila 1997; Peláez Rodríguez 2016). Thus, for immigrant women, the practice of caring for their children across borders with the help of female relatives (i.e., middle women) is marked by a messy process of gender resignification. That is, becoming transnational mothers deeply shakes and transforms their core identity as women and maternal subjects. While the trauma and pain of being apart from their children is real and long-lasting (and at times produces strained relationships between mothers and kids), transnational mothers might be able to reconcile being apart from their children and construct a positive narrative of their maternal role because they are able to economically support their kids (despite the sacrifice involved).

Ironically, it is perhaps through the very gendered assertion of motherhood as sacrifice that women who leave their children in their countries of origin can affirm themselves and push against normative conceptions of mothering. However, transnational motherhood in deportation presents new challenges for women who have experienced multiple expulsions or dislocations in a lifetime. It requires new conceptual frameworks and modalities or forms for telling their stories that are attentive to the deep textures of their realities as they (once again) try to recreate themselves and rebuild their communities aquí y allá.

Ana’s story of migration starts when she moved from Mexico City to Las Margaritas, Jalisco with her then husband. Historically, Jalisco has been one of the states with the highest migration to the U.S. (Durand, Massey, and Zenteno 2001). Though migratory patterns started to change during the 1980s, it is there that Ana became familiar with the dynamic of circular migration, as she witnessed mostly men from different small towns leaving and coming back. In Ana’s case, after marrying very young, becoming a teen mother, and ending an abusive and toxic marriage, she found herself struggling economically to support her four children. It was then that Ana met a new partner, a man who facilitated her migration to Chicago in 2001. Ana left her young children with her mother. La maternidad a distancia is at the core of Ana’s identity as a woman. Ana understands that distance, time, and other factors did not help her to have a strong relationship with her older daughters and son. But hopes that the distance produced by her deportation does not have the same impact on her relationship with her two younger sons who still live in Chicago. As she explains:

There are things that I keep to myself. But for instance, I have really enjoyed being the mom of [my two younger sons]; it has been easy. On the other hand, mothering [my four older children] is very heavy and, at times, very frustrating and very heavy. Very, very heavy. And it hurts because I love all six of them very much. And I wish life were different; unfortunately, I know this happened because I left them and because my children were raised by others. I often wonder how different things would have been if all my children had grown up with me. As a matter of fact, they would have a different life. It would be a very, very different life. And I think that is precisely what they reproach me: [They tell me] “our life would be very different if you had been here.” And I know that is probably true; but they must understand that we are not going to change the past. And that their lives can be different the day that they choose to make their lives different. I cannot change their childhood. We cannot do that. But they can be conscious adults who understand that their lives can be different right now, at this very moment if they decide to do things differently.

This is perhaps the ontological and ethical challenge that Peláez Rodríguez (2016) writes about in her work about how immigrant women try to re-signify motherhood after deportation. The moral harm of family separation in the context of deported mothers is in some cases experienced more than once. Thus, they are forced to relearn the meaning of their identity as mothers through multiple displacements in a lifetime. And while leaving one’s children to look for better opportunities does enable some immigrant women to structure their narrative around family separation in somewhat positive ways, there are ruptures, as Ana Laura mentions, that are often irreparable and that have long lasting effects on both parents and children.

There is both resonance and specificity in the experiences of the deported mothers we have met in Mexico City. For instance, Michelle (like Ana) was deported after living in the U.S. for more than a decade. But the first part of her story of migration resonates more with our stories, as she immigrated at the age of 5 with her mother in 1992 to Tulsa, Oklahoma. She finished high school in 2005 and started going to community college. But then she thought, “what’s the use?” As an undocumented student, she knew she couldn’t apply to many scholarships. This meant that a future post-community college was quite uncertain. Thus, she left for Mexico. In hindsight, she says, “era muy naïve, like, I was just tired.” Before leaving Tulsa, she didn’t research what she would need to enroll; and when she tried to enroll in a Mexican university, they asked her for documents that were notarized and apostilled. This was quite a common occurrence in Mexico when Michelle returned. The Mexican government believed that as returning citizens they did not encounter obstacles to getting identification cards or copies of birth certificates, something that became a Sisyphean task if anything was incorrect or incomplete or if a person had to travel to the specific location where they were registered as infants. And without the proper papers—and here there are resonances to the importance of papers for undocumented people in the United States—they cannot rent housing, get a job, get healthcare, or get an education. People like Michelle, who sought to enroll at the university, faced uphill battles in terms of getting transcripts validated and courses recognized since Mexico’s high school curriculum does not have anything comparable to U.S. courses like “social studies.” Although the Mexican government has passed federal legislation meant to remedy these issues, there are massive disparities from state to state (Garrido de la Calleja and Anderson, 2018).

After nine months of trying to enroll in college, Michelle decided to return to Tulsa. She had one failed attempt to enter the country. But she was successful on her second try and continued her life. Upon her return she became romantically involved with a Honduran man who was deported when she was six months pregnant. Nonetheless, she had the baby, and in 2010-2011 went back to community college. This time around, she heard about DREAM Act Tulsa, an affiliate of United We Dream, and got involved in organizing; she became so involved she put college on-hold again to dedicate herself to the movement and to advocate for a pathway to citizenship. She returned to community college in 2013. At that point, she was managing going to school, being a mom, and living with a Mexican American boyfriend who was physically abusive. During one of the many violent attacks, he hit her so hard he tore open her ear. Michelle filed a restraining order against him. Her peers in DREAM Act Tulsa, however, encouraged her to drop the restraining order. When Michelle went to get some belongings from his apartment, they got into an argument about the restraining order. He said it could negatively affect his future. At that point, she said, “fuck you” and he drop-kicked her. He dragged her through the apartment and started choking her. As everything started going black, she remembered she had his knife in her pocket, and she took a swing. A neighbor called the cops and she panicked. Michelle left the apartment. But a few hours later, she went to a women’s shelter. To her surprise, the cops were waiting for her.

Michelle was charged with a felony, and she took the plea. The criminal case was closed within a month; but the felony conviction meant that Michelle was deported with a lifetime ban, which meant leaving her only child with her mother. Five years passed before Michelle could hold her son again. In 2018, he was finally able to spend a few weeks in Mexico City. Though they chatted regularly via FaceTime, he didn’t recognize her when she went to pick him up at the airport. Her son’s reaction reminds us that despite the ways in which transnational motherhood pushes against normative notions of mothering, there are high emotional costs and ruptures that forced family separation and indocumentación produce. During that visit, Michelle had to tell her son that she had been deported because he thought she had just abandoned him. In Mexico City, she is now attending college and organizing for migrant rights again. Both school and activism give her purpose.

Domestic violence has played a big role in both Michelle’s and Ana’s lives. And in both cases, put them in situations that culminated in forms of displacement and precarity. Ana’s decision to divorce her physically abusive husband made her economically vulnerable, a situation that eventually set the stage for her migration to the U.S. In Michelle’s case, her actions, which were not recognized by the court as self-defense, led to her deportation. While Ana’s transnational motherhood has been structured first by migration and then deportation, Michelle experienced displacement as a young child. And like many undocumented children, she transitioned into an adulthood constricted by her legal status. When Michelle refused to be a victim of domestic violence, the patriarchal (and deporting) state failed to “protect” her. The experiences of undocumented and deported mothers render visible the ways in which the patriarchal state produces conditions of possibility for variegated forms of gender violence, witnessed through labor, economic and migratory polices, as well as domestic and sexual assault laws and penalties that frequently affect women negatively across borders (Fregoso 2003). But Michelle’s and Ana’s stories also reflect the ways in which activism has played a monumental role in their lives, helping them to reimagine themselves and challenge the very forms of violence that they have experienced in both the United States and Mexico.

May-June 2024 Series on Deportation and Coerced Return curated by Professor Perla M. Guerrero and Professor Gretel H. Vera Rosas.

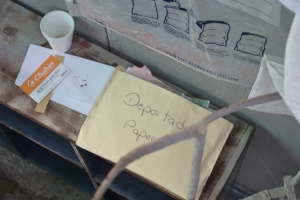

Photo at the top: Image 1. A map of the USA with names of family members and the places they live. Photo by Gretel Vera Rosas. CC BY-NC-ND

Read Part Two of this Essay Next Week on May 8, 2024

Works Cited

Abrego, Leisy. 2023. “Research as Accompaniment: Reflections on Objectivity, Ethics, and Emotions.” UCLA Previously Published Works.

Aparicio, Ana and et al. 2022. “Introduction.” In Ethnographic Refusals, Unruly Latinidades, xiii–xxxv. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

De Genova, Nicholas, and Nathalie Peutz, eds. 2010. The Deportation Regime: Sovereignty, Space, and the Freedom of Movement. Durham: Duke University Press.

Dreby, J. 2010. “Divided by Borders: Mexican Migrants and Their Children.” Berkeley: University of California Press.

Durand, Jorge, Douglas S. Massey, and Rene M. Zenteno. 2001. “Mexican immigration to the United States: Continuities and changes.” Latin American Research Review 36, 1:107-127.

Fregoso, Rosa Linda. 2003. MeXicana Encounters: The Making of Social Identities on the Borderlands.

Garrido de la Calleja, Carlos Alberto, and Jill Anderson. 2018. ¿Santuarios Educativos En Méxio? Proyectos y Propuestas Ante La Criminalización de Jóvenes Dreamers Retornados y Deportados. Xalapa, Veracruz, México: Universidad Veracruzana.

Goodman, Adam. 2021. The Deportation Machine: America’s Long History of Expelling Immigrants. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hester, Torrie. 2017. Deportation: The Origins of U.S. Policy. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Hondagneu-Sotelo, Pierrette, and Ernestine Avila. 1997. “‘I’m Here, but I’m There’: The Meanings of Latina Transnational Motherhood.” Gender and Society 11 (5): 548–71.

Huerta, Amarela Varela. 2018. “Migrants trapped in the Mexican vertical border.” Border Criminologies Blog.

Molina, Natalia. 2018. “Deportable Citizens: The Decoupling of Race and Citizenship in the Construction of the ‘Anchor Baby.’” In Deportation in the Americas : Histories of Exclusion and Resistance. Texas A&M University Press.

Montes, Veronica. 2013. “The Role of Emotions in the Construction of Masculinity: Guatemalan Migrant Men, Transnational Migration, and Family Relations.” Gender & Society 27 (4): 469–90.

Peláez Rodríguez, DC. 2016. “Stuck on This Side: Symbolic Dislocation of Motherhood due to Forced Family Separation in Mexican Women Deported to Tijuana.” Philosophy in the Contemporary World 23 (5): 5-21.

Reynolds, Tracey, Umut Erel, and Erene Kaptani. 2018. “Migrant Mothers: Performing Kin Work and Belonging across Private and Public Boundaries.” Families, Relationships and Societies 7 (3): 365–82.